And their jurisdictions stopped abruptly at their borders. More often than not, local police forces were hobbled by the lack of modern tools and training. Dealing with the bootlegging and speakeasies was challenging enough, but the “Roaring Twenties” also saw bank robbery, kidnapping, auto theft, gambling, and drug trafficking become increasingly common crimes. On the other side was law enforcement, which was outgunned (literally) and ill-prepared at this point in history to take on the surging national crime wave. By 1926, more than 12,000 murders were taking place every year across America. Rival gangs led by the powerful Al “Scarface” Capone and the hot-headed George “Bugs” Moran turned the city streets into a virtual war zone with their gangland clashes. With wallets bursting from bootlegging profits, gangs outfitted themselves with “Tommy” guns and operated with impunity by paying off politicians and police alike.

In one big city alone- Chicago-an estimated 1,300 gangs had spread like a deadly virus by the mid-1920s. There was no easy cure.

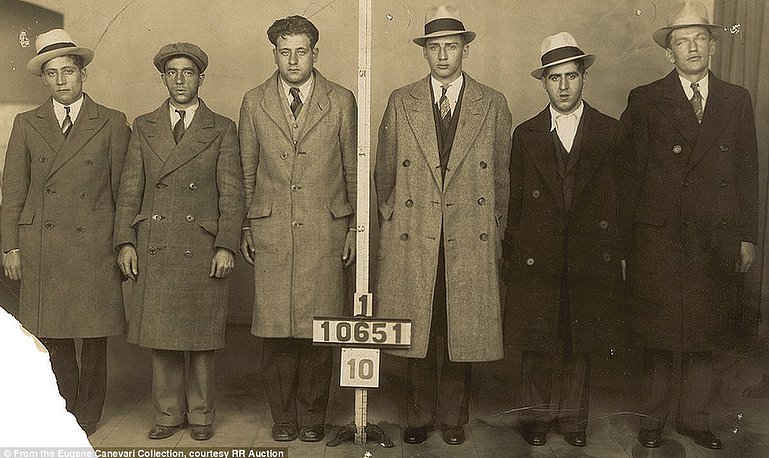

Chicago 1930 gangster activity professional#

On the one side was a rising tide of professional criminals, made richer and bolder by Prohibition, which had turned the nation “dry” in 1920. It wasn’t much of a fight, really-at least at the start. The FBI and the American Gangster, 1924-1938, FBI.gov.Īmerican History: The Great Depression: Gangsters and G-Men, John Jay College of Criminal Justice.īarry Latzer, “Do hard times spark more crime?” Los Angeles Times (January 24, 2014).īryan Burrough, Public Enemies: America’s Greatest Crime Wave and the Birth of the FBI, 1933-34 (New York: Penguin Books, 2004).The “war to end all wars” was over, but a new one was just beginning-on the streets of America. economy stalled again in 1937-38, homicide rates kept falling, reaching 6.4 per 100,000 by the end of the decade. New Deal programs were likely a major factor in declining crime rates, as was the end of Prohibition and a slowdown of immigration and migration of people from rural America to northern cities, all of which reduced urban crime rates. As the economy showed signs of recovery in 1934-37, the homicide rate went down by 20 percent. Violent crime rates may have risen at first during the Depression (in 1933, nationwide homicide mortality rate hit a high for the century until that point, at 9.7 per 100,000 people) but the trend did not continue throughout the decade. Effects of New Deal and Falling Crime Rates in Late 1930s By the end of 1934, many high-profile outlaws had been killed or captured, and Hollywood was glorifying Hoover and his “G-men” in their own movies. Cummings, became law in 1934, and Congress granted FBI agents the authority to carry guns and make arrests. Roosevelt and his attorney general, Homer S. Many Americans who had lost confidence in their government, and especially in their banks, saw these daring figures as outlaw heroes, even as the FBI included them on its new “Public Enemies” list.īut after the so-called Kansas City Massacre in June 1933, in which three gunmen fatally ambushed a group of unarmed police officers and FBI agents escorting bank robber Frank Nash back to prison, the public seemed to welcome a full-fledged war on crime.Ī new anti-crime package spearheaded by President Franklin D. Edgar Hoover.Īt the same time, colorful figures like John Dillinger, Charles “Pretty Boy” Floyd, George “Machine Gun” Kelly, Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker, “Baby Face” Nelson and “Ma” Barker and her sons were committing a wave of bank robberies and other crimes across the country. Amidst a media frenzy, the Lindbergh Law, passed in 1932, increased the jurisdiction of the relatively new Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and its hard-charging director, J. The kidnapping and murder of the infant son of Charles Lindbergh in 1931 increased the growing sense of lawlessness in the Depression era. What Role Did Women Play in Ancient Rome? Public Enemies and G-Men

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)